Background

Introduction

In China, during the long historical period between the invention of writing and the spread of telegraphy in late-Qing China in the nineteenth century, and probably long afterward, letter writing was the most used medium of written communication between educated individuals. The social practices of letter-writing were never stagnant and had enormous impact on the lives and culture of the elites. Earliest material evidence of letter writing in China can be traced back to as early as 224 BCE,[1] and the epistolary tradition has lived on even after being superseded by newer technologies in the 1990s.

I focus on the Song dynasty in Chinese history, an era in which almost all realms of the arts flourished and a community of literati scholars dominated the cultural and political scene. During the Song, letters not only became an increasingly important and sophisticated literary genre, but also were a crucial element in the construction of a common cultural knowledge, a medium of transmission for philosophical and religious ideas, material for publications, and above all—as always—an important medium of communication for the elite. Every government official was required to be literate and able to write letters and other documents, so the writing and reading of epistolary texts was an indispensable part of the daily lives of literati officials in Song China.

The Existing Literature: Traditional Studies

However, researchers have not yet thoroughly looked into written correspondence from that time, either as a major medium of communication in history or as an important literary genre in its own right. As scholar Antje Richter explains, “in China, letters are still rarely perceived as a genre that needs and deserves to be treated on its own in order to realize its potential. Letters are utterly marginal, and if they are mentioned in more general literary scholarship at all… there is no reflection on the epistolary character of these texts.”[2] Letters also had no significant role in the Confucian canon. It is astonishing that, although the writing and reading of epistolary communication were an indispensable part of the daily lives of cultural elites in premodern China, the number of academic studies on all Chinese letters from every historical period taken together is still far exceeded by academic writings on the epistles by any of the important individual authors from the European tradition, such as the Pauline epistles or letters by Cicero.[3]

In regard to the existing literature about letter writing in traditional China, scholar Zhao Shugong’s history of epistolary literature is among the first attempts to tackle the topic from a modern perspective. Since his survey covers a much broader period of time, his discussion of Song writers is very brief.[4] Zhao also takes epistolary sub-genres to be relatively fixed, in contrast to the dynamic nature of the various epistolary sub-genres. Meanwhile, Zeng Zaozhuang, in his detailed study of Song prose, has outlined the characteristics of and common topics covered in epistolary sub-genres, laying the basis for a better understanding of the genre as a whole.[5] Also, the Western encyclopedic work and the first study of Chinese epistolary literature and culture in its entirety in any language, entitled A History of Chinese Letters and Epistolary Culture and edited by Antje Richter, has just been published. Its wide-ranging articles show capably the multiplicity and diversity of Chinese epistolary culture.[6] As far as I am aware, the first systematic study devoted exclusively to letters from Song China is a 2008 PhD dissertation by Jin Chuandao.[7] It contains many useful insights into the features of letter writing in this period, especially with reference to the more important literary figures as case studies.

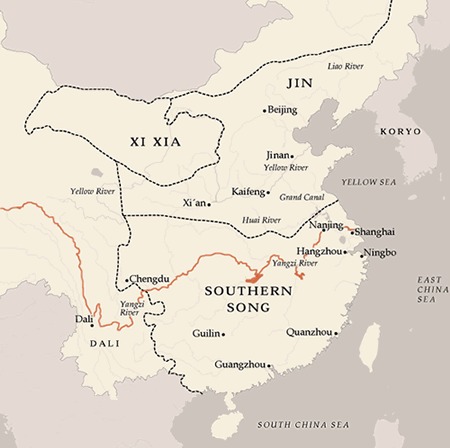

While his attention is devoted to collections that contain texts by Northern Song authors, my thesis extends to letters from the period after the southward move of the Song court in the early twelfth century—a time that, according to many historians, saw profound social changes impacting communication among scholar officials. With networks among the literati expanding and gaining more profound roots in local society in the twelfth century onwards, communication among the literati is likely to reflect these changes, as some historians have suggested.[8] Relative to the era that preceded the move to the south, did literati officials under the Southern Song write more eagerly and frequently to acquaintances from their natal places? Can we see a growing eagerness to engage in conversations with other individuals within the locality rather than with those at the central court, as a consequence of the elites’ strategies proposed in the “localist (or localization) paradigm” in historical research on middle period China? Or was there a more urgent need to write across regions to keep in touch and foster horizontal connections with colleagues far away, especially in order to stay abreast of political developments throughout the much reduced Chinese empire?

The Existing Literature: Digital Explorations

There has been some experimentation with the application of these methods to Song letters and networks, and the results suggest that there is much more that is worth exploring in future research. With more digital datasets on epistolary material becoming available (due to large digitization projects, such as the China Biographical Database), digital methods are becoming ever more effective in handling large amounts of data from disparate historical sources. Digital tools should complement the traditional historical and philological methods and will allow a more extensive analysis of letters.

A 2007 conference paper by sinologist Hilde De Weerdt (who also supervised my doctorate on letter writing) represents one of earliest attempts to map correspondence networks, as far as I know.[9] Her pilot project is to focus on a locality, Mingzhou, in coastal China. It was almost a failed attempt, however, because there was simply too little data to yield any real results. Her paper exposes the nature and also the limitations of CBDB data (as of the time she wrote this paper), which is of course very important for my inquiry. Luckily we have more epistolary data in digital form now; my task is to explore how I

The designer of the structure of the China Biographical Database (CBDB), Michael A. Fuller, has later tried to use some parts of the epistolary data that I have shown in class to produce some visualizations. Letter exchanges are a kind of social association between people in the data of CBDB, and a conference presentation of his “Initial Perspective on Song Dynasty Letters using CBDB” involved putting epistolary data within larger social contexts supported by data in it.[10] In order to make the results more manageable, he broke the data from Song China into 4 time periods: 935-1040, 1041-1130, 1131-1220, and 1221-1387. The data contains 2,506 people and 4,652 letters. This is a meaningful exploration in visualizing and presenting correspondence networks but it has not yielded any concrete results yet in terms of historical analysis. My proposed project will hopefully use digital tools to combine the epistolary data with more biographical information, such as to map the geographical locations of postings of letter writers. This should enable me to identify interesting patterns and focus further on certain subsets of the data in my analyses.

I have chosen to exclude the discussion of digital projects studying correspondence from other cultures for they are too numerous to cover here. This is of course not to say that they will not provide inspiration for my study here.

[1] Antje Richter, Letter and Epistolary Culture in Early Medieval China (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2013), 18-20.

[2] Richter, Letter and Epistolary Culture in Early Medieval China, 7.

[3] See Ibid., 5-6.

[4] Zhao Shugong 赵树功, Zhongguo chidu wenxue shi 中国尺牍文学史 (Shijiazhuang: Hebei renmin chubanshe, 1999).

[5] Zeng Zaozhuang 曾枣庄, Song wen tonglun 宋文通论 (Shanghai: Shanghai renmin chubanshe, 2008), 779-827.

[6] A History of Chinese Letters and Epistolary Culture, ed. Antje Richter (Leiden: Brill, 2015), 363-97.

[7] Jin Chuandao 金传道, “Bei-Song shuxin yanjiu 北宋书信研究,” Ph. D. diss., Fudan University, 2008.

[8] See, among many others, Robert P. Hymes, Statesmen and Gentlemen: The Elite of Fu-chou, Chiang-hsi, in Northern and Southern Sung (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1986)

[9] Hilde De Weerdt, “Mapping Communication from Mingzhou: Networks of Correspondence,” paper presented at “Prosopography of Middle Period China: Using the Chinese Biographical Database” Workshop, Warwick, Dec. 2007.

[10] Michael A. Fuller, “Prosopographical Perspectives on Letter Writing during the Song: The View from the China Biographical Database (CBDB),” presentation at “Letters and Notebooks as Sources for Elite Communication in Chinese History, 900–1300” conference, Oxford, Jan. 2014. See conference report here.